I love outliers. That’s why Gwenifer Raymond drew me in: How improbable is a Goth-looking young lady from Wales picking a Depression-era parlor guitar in the American Primitive style pioneered in the Sixties by John Fahey? You couldn’t possibly make her up, or the fact that she arrived at her unlikely choice of genre via an early exposure to Nirvana.

“When I was about eight years old a pretty formative thing happened to me,” Raymond writes in her bio. “My mum bought me a cassette tape of Nirvana’s Nevermind. …I spent many hours hyperactively running around the house with headphones on, volume at full blast, and Nevermind on repeat. It was either for Christmas or my birthday that year that I asked for a guitar.”

As a teen Raymond played guitar and drums in punk bands “around the Welsh valleys,” she writes, but adds: “I was also getting seriously into older stuff, Dylan, The Velvet Underground and the like. Through those cheap compilation CDs you could get then, I found that a common influence amongst these guys was pre-War Delta and country blues, as well as Appalachian music. Eventually I stumbled upon Mississippi John Hurt, Skip James and Roscoe Holcomb, and they became the holy trinity of musicians I so wanted to able to play like. Eventually, I tracked down a blues man in Cardiff who could teach me and it was in studying these guys that I was introduced to John Fahey and the whole American Primitive thing.

“American Primitive was the first time it had occurred to me that you didn’t really need anything more than one solo instrument to fully express yourself, especially when those feelings and moods refuse to be articulated in words, sometimes it’s a mystery to yourself what it is you’re expressing. …in the end I think that all these things are really part of a circle, feeding back into itself. It’s all just a lineup of strange mutations.”

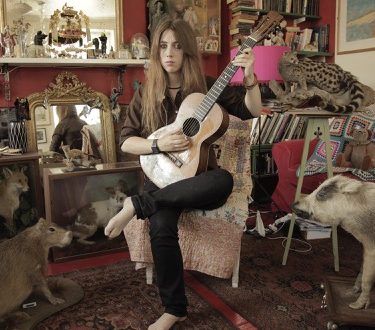

Strange indeed! The video for Raymond’s “Sometimes There’s Blood” finds her picking a 1930s Harmony Supertone Bradley Kincaid model Houn’ Dog guitar tuned to the D minor tuning (D-A-D-F-A-D) John Fahey learned from Skip James, in whose rediscovery Fahey played a key role. Raymond plays surrounded by a menacing menagerie of stuffed mammals. Her deadpan demeanor, broken by occasional nervous sidelong glances at the beasts, adds humor to the anxious energy of her composition. It’s propulsive but dark in a distinctly Fahey-esque manner, with hints of Roscoe Holcomb’s `high lonesome sound’ offered for good measure.

Raymond also has a handle on the old-timey frailing banjo style, which she can deliver at a breakneck pace.

Raymond’s website proclaims her a “guitar convincer, banjo thumber, American Primitive musician.” Her debut album, to be released June 29th, is Gwenifer Raymond: You Never Were Much of a Dancer on Tompkins Square (TSQ 5562). It offers thirteen instrumentals, most composed by Raymond, played on guitar and banjo (plus one brief outing on fiddle). Her titles-the album opens with “Off to See the Hangman, Part I” and closes with “It Was All Sackcloth and Ashes”—suggest these generally aren’t the sunniest tunes: Raymond has a strong feel for the dark and stark character running through the American Primitive genre. It’s a rarefied stream in which few women have ever chosen to swim, and Raymond is already making waves. On April 23rd, she made this Facebook post:

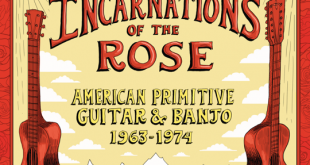

“About two weeks ago I set out for the USA for the first time in my life. Josh Rosenthal [of Tompkins Square] convinced me to drag myself to The Thousand Incarnations of the Rose festival that was happening in Takoma Park: the first its kind, a three days fest featuring dozens of American Primitive musicians, from across the breadth of its eras – mightily put together by Jesse Sheppard and Glenn Jones.

Through some unique madness I got to play amongst great bloody giants of guitar and banjo, I got to hang out with Joe Bussard and listen to his records and pet his dogs, and I met a whole lot of absolutely top quality humans.

I don’t quite know how that happened, but I’d sure like it to happen again. (Also…Henry Kaiser just damn up and gave me a guitar from 1890…He is a goddamn dude.)”

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California