“Be proud that you’re Indian, but be careful who you tell.”

-Robbie Robertson, Mohawk, in Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World

It’s an irony of exclusion that those shut out of mainstream opportunities often have disproportionate impact on popular culture, especially music. From late 19th century Irish and Jewish vaudevillians to the same era’s black ragtime composers and up to the present day, it’s cliché that those marginalized from conventional power and prestige often break social barriers via entertainment, especially music.

But what of America’s first people? What have Native Americans given to American popular music? A lot, answers the film Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked the World. Rumble is a provocative challenge to the notion that American music is exclusively a blend of evolving European and African traditions. The land’s first people also contributed, and Rumble offers choice and surprising examples.

The most colorful is the Mardi Gras Indians, who parade and sing in elaborate feathered finery. Generally regarded as an example of Afro-Caribbean culture unique here to that atypical Southern city of New Orleans, Rumble argues that the mingling of African slaves and indigenous people played a role in shaping Mardi Gras Indian culture. “It’s a gumbo,” one remarks, and its Native American flavor may be more than mere feathers.

Mississippi was home to the Choctaw before their forced removal to Indian Territory. It was also home to the blues, and Rumble argues that the archetypal Delta bluesman Charley Patton voiced Native American roots in the way he sang and played. “He played his guitar like a drum,” notes contemporary blues artist Corey Harris, drumming being central to both African and Native American music. Though of very mixed ethnicity, the light-skinned Patton is often cited as exemplifying African roots in the blues tradition. Rumble challenges that assumption in a striking scene where Native American singer Pura Fé listens to a 1929 Patton recording and points out what she hears as Indian vocal traits. Is it time to rewrite the blues history books?

Far from the South in Idaho, the Coeur d’Alene Indian tribe gave the Swing era one of its great vocalists, Mildred Bailey. Tony Bennett makes a touching appearance in which he, at age 88, testifies to being a lifelong fan of Bailey’s phrasing. An ethnomusicologist then argues that the indigenous songs she heard as a child may have inspired the way Bailey sang.

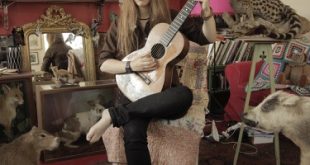

The other woman in the film is Buffy Sainte-Marie, a Cree from Canada who wrote some stinging topical songs in the 1960s. Surprisingly the film does not showcase her Indian rights anthem, “Now That the Buffalo’s Gone.” From the same era and folk scene came Peter La Farge, who appears too briefly in a war bonnet singing “Custer,” one of the La Farge songs Johnny Cash recorded on his controversial Bitter Tears album.

Protest was not the goal of the band Redbone, which appeared in full Indian regalia (and even did a stomp dance) while performing its `70s hit “Come and Get Your Love.” The band’s Pat Vegas says they followed the advice of Jimi Hendrix, who told them: “Do the Indian thing.” Hendrix is among several artists of mixed ethnicity who is shown in a light featuring the influence of Indian heritage on his personality and music.

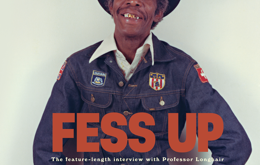

Directed by Catherine Bainbridge and co-director Alfonso Malorna, Rumble is episodic in nature and may be a couple of episodes too long. Still, it’s easy to see why it was hard to leave anything out, ranging as it does from the rootsy (Mardi Gras Indians, Patton) to the recent (Taboo of the Black Eyed Peas). I could have lived without the metal acts, but since Apache rock guitarist Stevie Salas is one of the film’s executive producers, that’s all in the family, too. The tragic tale of Kiowa guitarist Jesse Ed Davis delivers the film’s most gripping episode, and Band guitarist Robbie Robertson is articulate and engaging throughout.

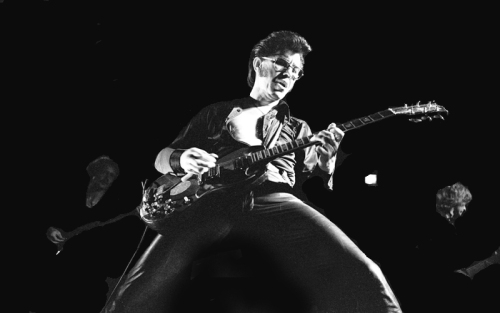

The film opens and closes with the sounds of the Shawnee guitarist-bandleader Link Wray, whose 1958 instrumental gives the film its name. “This is where it started,” Guns `n Roses guitarist Slash says of “Rumble,” which the film claims was the only instrumental ever banned from radio. Trying to play something over the rhythm associated with “The Stroll,” Wray came up with the first power chord rock performance. Iggy Pop and a host of others extol what one calls `the theme song of juvenile delinquency,’ and there’s fine footage of Wray swaggering as he plays “Rumble.” No one mentions one of the legends surrounding the distorted, blown-speaker sound of the 1958 recording, but as the end credits roll and we hear “Rumble” again, an actor as Wray demonstrates it: in his little backwoods North Carolina studio he takes a screw driver and punctures his amp’s speaker, thus unleashing the dirty sound of “Rumble.”

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California