New Orleans, cradle of jazz, evokes brass over any other sort of instrument for most of us—naturally, given the fame of its parading brass bands and the trumpet of its iconic native son Louis Armstrong. But for a century it was also a piano town. “New Orleans was the stomping grounds for all the greatest pianists in the country,” Jelly Roll Morton recalled in Alan Lomax’s book Mr. Jelly Roll (1950). Looking back at the early days of the 20th century, Morton said: “We had them from all parts of the world, because there were more jobs for pianists than any other ten places in the world. The sporting houses needed professors, and we had so many different styles that whenever you came to New Orleans, it wouldn’t make any difference that you just came from Paris or any part of England, Europe, any place—whatever your tunes were over there, we played them in New Orleans.”

In the documentary Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together, elder statesman Isidore `Tuts’ Washington talks about the range of styles in which a successful Crescent City pianist had to be fluent: he demonstrates what he calls classical by playing “Russian Lullaby.” His pupil, Henry Roeland Byrd, AKA Professor Longhair or Fess, sits at a keyboard and shows how Calypso and rhumba influenced his distinctive approach, one enhanced by lessons in articulation learned from Tuts (“Clean notes, no smears”). The artist who took their influence into the pop mainstream, Allen Toussaint, demonstrates how he reworked Longhair’s style in a rockin’ instrumental, “Whirlaway,” while comparing his mentor to Edison for his inventiveness.

The late filmmaker Stevenson J. Palfi created a rare gem of a documentary in his 1982 film Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together. The casual intimacy with which his subjects reveal themselves and their music shows how thoroughly they trusted Palfi. We’ve become so accustomed to the `talking head’ school of documentaries in which `authorities’ appear to contextualize all we see that it’s both startling and refreshing to watch a documentary in which the talking heads are actually the subjects of the film. Washington, Byrd and Toussaint were all articulate and needed no one else to explain them or their music. Without being didactic, they demonstrate and discuss at their pianos. Byrd’s wife Alice appears and talks about his gift, but hearing Byrd discuss his music, it’s clear a conscious craftsman was shaping his sound.

The film opens with the subjects playing “Pinetop’s Boogie Woogie” on three adjacent pianos, Tuts on the near end, Byrd on the far, and Toussaint in between. Unseen, we hear the filmmaker voice a brief set up: “Originally, this started out to be a performance by three gifted New Orleans piano players who influenced each other’s music featuring each executing his individual style, culminating with all three playing a number together. It evolved, however, into a more intimate and complex story.” Then we hear Tuts recall an underage Byrd sneaking into a “joint called the Cotton Club on Rampart” to hear him play, intercut with Byrd demonstrating the first thing he learned from Tuts. Palfi was a master at narrative editing: the three artists’ interwoven musical journeys are clearly mapped at the outset.

The film’s theme is stated in its title. There’s some uncertainty among the subjects as to whether a piano trio performance is really a good idea: “Piano players rarely ever play together,” Toussaint cautions. But after some wonderful performances establishing who they individually are—Tuts at a club playing a vintage Pete Johnson boogie woogie, Byrd on TV’s Soundstage being introduced by Dr. John as “the originator of rock `n roll,” Toussaint in the studio working on an album with some of the Crescent City’s best musicians—we see the three pianists rehearsing together. Byrd takes charge of the session casually but authoritatively, cuing both his mentor and his disciple on when to solo, when to pass the baton. There’s a wonderful shot of Byrd observing it come together with a satisfied, beatific smile.

The point of the rehearsal was for a joint performance by three generations of New Orleans pianists. Up to this point most of the film has been shot indoors and has focused on the three pianists. The mood and tone of the film shifts abruptly with Byrd’s death three days prior to the scheduled performance. Suddenly we’re outdoors, hearing from Byrd’s neighbors and fans about their sense of loss, waiting for his funeral. Footage of the funeral and wake reflect the range of Byrd’s impact within his community and beyond: he’s eulogized both by an emotional preacher and by Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler. Toussaint performs a tribute to Byrd reworking some of his signature piano figures. Then we’re outdoors in a chaotic crowd as the coffin is borne out for the second line parade to the cemetery.

Tuts and Toussaint proceed with a performance as a tribute to Byrd. Tuts says they’ll play the first song he taught Byrd, “Junker’s Blues,” which, he adds, no one had recorded. (Actually another native New Orleans pianist, Champion Jack Dupree, recorded it in 1940.) We see the 73-year-old Tuts in his black suit at a piano back to back with a brilliantly gold suited Toussaint, then 42, playing at another. A giant image of Byrd, AKA Professor Longhair, looms behind and between them.

Piano Players Rarely Ever Play Together is more than a love letter to three great New Orleans pianists: it’s an insightful reflection of a musical community and of the process of making music, demonstrated and explained by the musicians themselves. It’s obvious that the filmmaker, who shot the players and keyboards from sundry angles, loved pianos, their physicality and their music. Palfi’s editing, a comment by Byrd dovetailing with an illustration by Toussaint leading to something further from Tuts, is remarkable. It illustrates that the strength of a documentary is as much in its pre-production (here gaining the confidence of the film’s subjects) and post-production (meticulous editing) as its actual footage. It’s obvious a lot of passion went into Piano Players: I wish there were more music docs like it.

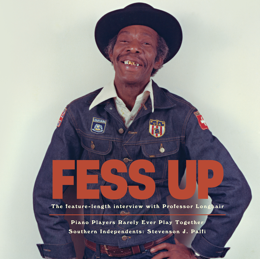

Piano Players is the crown jewel in a double DVD package with a 37-page book (released in April to coincide with Jazz Fest in New Orleans) called Fess Up. It’s complemented by insightful excerpts from a 1987 documentary by Mark J. Sindler and Al Godoy, Southern Independents: Stevenson J. Palfi. “I hope viewers come away with a sense of the joy and hardship of making music,” Palfi says of Piano Players and his other documentaries. He talks about Piano Players being “a full-time obsession” for two-and-a-half years: “I spent fourteen hours a day editing,” he says, comparing his work to that of a marathon runner. But the loneliness of the long distance editor did not make him meek: Palfi went toe to toe with his subjects when needed. Toussaint was ready to throw in the towel when he felt the rehearsals weren’t coming together and went in to the control room to vent to Palfi. Toussaint was coolly told to go back out and make it come together. For an impoverished indie filmmaker to say that to someone with Toussaint’s wall of gold records took guts.

The second DVD in the Fess Up set is a 95-minute interview with Byrd conducted on Jan. 28, 1980, two days before his death. You’d never know it: he appears hail and hearty, if older than his 61 years. Byrd talks about a multi-instrumentalist mother who performed in sideshows before retreating to the church and about learning to repair junked pianos as a kid, about the time he got his first performance experience playing for change in a `spasm band.’ He reveals that the `Spanish tinge’ (a Jelly Roll Morton term) in his music came not from New Orleans but from working with Hispanic and Jamaican musicians while in the Depression-era Civilian Conservation Corps. Byrd tells how he came to be called Professor Longhair after having briefly been Little Lovin’ Henry and Whirlwind, his name as boxer. He was also a gambler and cook before making his first recordings as Professor Longhair and His Shuffling Hungarians. He talks, without bitterness but with frankness, about the hardship of trying to survive as a musician and of hanging it up for nearly a decade. He says he was sweeping floors in a Rampart St. record store when he was rediscovered. And he explains the sources of his signature song, “Tipitina,” both its name and its music. (The interview was recorded in the club named for it, Tipitina’s.) Perhaps best of all, Byrd demos what he calls his `gimmicks’ on piano and goes through some of his best known works: we see his hands and keyboard reflected in his sunglasses as the camera takes an extreme close-up while Byrd plays “In the Night.” “I do know what I’m doing,” he says. “I’m about the only one doing it.” This long interview is a fascinating document, one surely no one involved suspected would become his Last Testament.

There is a wealth of great photos in the set’s 37-page book, as well as essays by Johnny Harper, Bruce Raeburn, and Michael Oliver-Goodwin. The last is an insightful 1984 review of the film for The Village Voice in which Oliver-Goodwin wrote: “Each of these artists added to the cultural treasure he received, and passed it on to the next. If the main metaphor of Piano Players lies in the painful difficulty of playing together…, its true center is the mutual respect and secret history these artists share.”

You can watch a trailer of Piano Players below. Out of print since the days of VHS tape, and get more info on the Fess Up package here.

https://youtu.be/aW5WORGKJ_E

It can also be ordered directly here.

In context of reviewing documentaries about New Orleans piano masters I would be remiss in not mentioning an excellent one that came to DVD in 2016, Bayou Maharajah: The Life and Music of New Orleans Piano Legend James Booker. Director Lily Keber turned her obsession with Booker’s legend into a bittersweet love letter to an artist who had been dead nearly 30 years by the time she made her film. Booker was a tragic savant who transcended the New Orleans piano tradition while being very much a part of it. “I can’t get away from New Orleans,” we hear Booker say, yet his extraordinary technique and imagination took the Crescent City keyboard sound where it had never gone before. Keber interweaves gorgeously shot performance footage of Booker in Europe with stock footage evocative of places in his life’s journey alongside interviews with those who worked with him. Throughout, Booker’s music is a nonstop soundtrack.

Booker was a child prodigy who made his first record at 14. “He was our musical hero,” saxophonist Charles Neville says. “He was the cat who could play with anybody.” He was touring while still in his teens and would back up everyone from Aretha Franklin to Dizzy Gillespie to the Doobie Brothers. Classically trained and with huge spidery fingers, Booker could play some of everything and had a knack for making it all sound uniquely his own. Sadly, his staggering talent was undermined by a host of substance abuse and mental health issues. He was almost a textbook example of the genius-madness paradigm. In liner notes to one of his albums, he wrote: “To know the feeling of rejoicing in sorrow is nothing strange to me.”

But don’t take that to mean Bayou Maharajah is a downer. Many of the anecdotes of Booker’s friends and musical comrades are hilarious. Booker is both dazzling at the piano and exudes a puckish charm in the performance footage. The wealth of photos we see of him in varied garbs suggest someone with genuine joie de vivre and no excess of ego. That’s in his music and off-the-wall lyrics, too: actor/musician Hugh Laurie marvels at the “joy, wit, intelligence and sheer bloody mayhem” he hears in Booker’s playing and songs.

One of the sweetly surprising twists in Booker’s story was his role as mentor to a young Harry Connick, Jr., who remembers Booker with great affection: “He was like the favorite uncle you didn’t see that often,” he says in the film.

“In New Orleans they call me the Piano Prince,” Booker tells an audience at the start of the film. At the end we see it written on his tombstone. Dead at 43, Booker remains an enigma, that rare Outsider Artist who got a shot at stardom. In the 24-page book with the DVD, Stephen F. Rose writes: “It is not easy to classify Booker. He was a junkie, sexually ambiguous, and disabled. He likely suffered from one or more psychological conditions. But he was also a virtuoso and a genius. The connections he made on the keyboard remain original, idiosyncratic: he is a genre all of his own.”

Along with Keber’s award-winning Bayou Maharajah documentary, this DVD offers an `extra’ of eight notable pianists, Dr. John, Harry Connick, Jr., and George Winston among them, discussing and demonstrating what made Booker’s playing so dazzlingly unique. Several show how his classical training contributed to his style, though what he did with it was uniquely his own. “He wasn’t showing you he could play Chopin,” Hugh Laurie wryly observes. “He was showing you that Chopin, if he were lucky, would’ve gotten to write for James Booker.” Allen Toussaint likens his old friend to composers of Chopin’s stature, and advises anyone seeking a thorough musical education: “You wouldn’t want to miss Booker.” Here’s the site for more about Bayou Maharajah.

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California