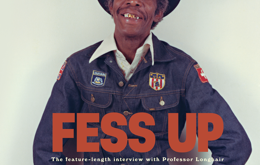

He was the sort of guy who never met a stranger and toured the world while staying deeply grounded in his culture. He was the least full of himself performer I ever met, blessed with an impish sense of humor and big infectious grin. Today I revisited some Lps he had long ago autographed for me when I got the news of his passing. D.L. Menard (April 14, 1932-July 27, 2017) was a native of Erath, Louisiana, a community in which he spent his 85 years while still managing to tour some 38 countries and play dances and festivals across America. He grew up on a farm speaking Cajun French but loved the honky-tonk country sounds new to radio when he was in his teens. Hank Williams especially impressed the young D.L. (for Doris Leon), who developed his own version of Hank’s pungent twang. He was still a teen when he was hired to play guitar and sing in the Louisiana Aces, in part for for his ability to sing in English.

But a song he wrote in French became his claim to fame. He was pumping gas (being a Louisiana Ace didn’t pay the bills) when the comic-awful saga of a man trying to sneak into his house after an all-nighter came to him. The sly, self-deprecating lyrics and catchy dance tune were firmly in the Hank tradition, but the year was 1962. Artists like Rusty and Doug Kershaw were mainstreaming Cajun music for country radio. Louisiana Aces bandleader Elias Badeaux didn’t think the song was even worth recording at a session the Aces had lined up for the Swallow label, but D.L. pulled rank and played it for label owner Floyd Soileau, who heard its potential. “La Porte en Arriere (the Back Door)” not only got recorded, it quickly became a regional hit. Over time it also became a standard every Cajun band had to play, and the guy who cut it, Floyd Soileu, later said: “‘The Back Door’ is the anthem for Cajuns today. Everybody knows it. Everybody loves it.”

Still, Cajun anthems do not an international career make. I know neither the catalyst nor the chronology, but somehow at sometime D.L. became a mainstay of the national folk festival circuit and a popular artist on State Department-sponsored international tours. If I had to guess I imagine the generous hand of Dewey Balfa may have worked on D.L.’s behalf: Dewey and the Balfa Brothers had made that journey before him. Whatever put him before broader audiences, D.L. was ready for the opportunity. He was a dependable performer who was both earthily charismatic and mischievously funny onstage. He was garrulous with both his fellow musicians and fans. No doubt the tours were wearing, but D.L. never appeared irritated or exhausted. Odds are he considered himself lucky to no longer be a pump jockey. In the liner notes to his Rounder album, No Matter Where You At, There, You Are, D.L. wrote: “Most of the people seem to view us now as professional musicians, not just as people playing for the fun of it…But that won’t stop us from playing the kind of music you like, or singing a song that you like to hear.”

D.L. did a lot of that when I got to hear him with various accompanying musicians in Southern California in the late 1980s. It was a time when Cajun and Zydeco music were enjoying a brief national vogue: remember Rockin’ Sidney’s “Don’t Mess with My Toot Toot?” If Zydeco mixed Creole music with R&B, D.L. mixed Cajun music with classic country. They didn’t call him `the Cajun Hank Williams’ in Louisiana for nothing: D.L. could amp up an urgent sense of pathos alongside the best hardcore country belters. Ricky Skaggs recalled getting chill bumps the first time he heard D.L. sing Hank Williams’ “House of Gold.” Watching D.L. sing a song like that onstage, you knew he wasn’t faking: his eyes shut hard, his well-lined face tightened to a grimace, and a knife blade of a voice vaulted out to stab you to the heart. Then his next song would be smiles, good times and two-steps.

I had the pleasure of visiting D.L. and his late wife Louella once at their Erath home, but my most vivid memories of D.L. are of his visits to California and my between-set conversations with him. In one he recounted how he had, after a lifetime of smoking, recently quit cold turkey: “Cigarettes didn’t dope me,” he said, meaning he had the upper hand of his habit. D.L. had an original way of turning phrases in his second language. He was also a talented craftsman, famous for the ash-wood chairs he made by hand. His folk talents, notably his musical ones, were acknowledged in 1994 when he was given the National Heritage Fellowship Award by the National Endowment for the Arts. Among them was his rock solid rhythm guitar playing, an important talent for someone fronting a band.

On July 2nd, D.L.’s hometown of Erath honored the 55th anniversary of “La Porte en Arriere (the Back Door)” and the native son who wrote and recorded it. D.L. made what was likely his last public performance that day, witnessing the unveiling of a handsome portrait destined for his hometown’s Acadiana Museum. No doubt his neighbors now share D.L. stories as they celebrate his long and well-lived life. They aren’t alone: Many across America and in countries across the globe were touched by the music and winning personality of D.L. Menard, someone I will always remember with a puckish glint in his eye and a voice hardwired to his heart.

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California