San Antonio’s Gunter Hotel is haunted. The ghost is believed to be a woman murdered and dismembered there in 1965. She is nameless–her remains were never found–but her restless spirit has shaken enough subsequent guests to become part of San Antonio folklore. The specter most associated with the hotel is no former guest: he couldn’t have lodged there in the segregated 1930s. He probably spent no more than a few hours at the Gunter over the course of three days. He got in (likely via the servants’ entrance) to record. No one has reported seeing Robert Johnson’s ghost at the Gunter, though the hotel would welcome the publicity. It already has a Johnson-themed bar named for the room where he reportedly recorded, Bar 414, and a plaque in its lobby proclaiming:

“The GUNTER HOTEL is renowned as one of a few remaining area locations that served the recording industry in the 1930s by providing suitable accommodations to record Hillbilly, Blues, Jazz and Mexican ethnic music…. High on the list of legendary artists who recorded here is the bluesman ROBERT JOHNSON. During Thanksgiving week of 1936, the American Record Corporation held three sessions with Johnson at the Gunter Hotel during which he recorded some of his most strikingly original compositions…Those recordings influenced his contemporaries as well as generations of musicians to come…and earned ROBERT JOHNSON his place of honor among the first five forefathers inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.”

His induction came in 1986, a half century after Johnson’s Gunter Hotel recording debut and four years before the boxed set, Robert Johnson: The Complete Recordings, brought his music to a then-new medium, the compact disc. It sold well over a million copies worldwide and won a Grammy for Best Historical Album. At the dawn of the 1990s, Robert Johnson was a rock star. Now, more than a quarter century later, does anyone still care about Johnson? It’s hard to imagine his work ever again enjoying the mass popularity of the 1990 Complete Recordings box. It was a rare convergence of factors that made that happen: Big name rockers (notably the Rolling Stones and Cream) had been covering Johnson’s songs since the late `60s, lending his original recordings a cachet of hipness. His short life was shrouded in mystery and Faustian legend, making his songs a Rorschach test and their singer a Byronic hero. The compact disc, hailed as a magic medium that made the old and scratchy sound fresh and flawless, was still new in 1990. The novelty of `old wine in new bottles,’ coupled with romantic fantasies and reflected rock stardom, made an unlikely hit of Johnson’s Complete Recordings.

Adding to the anomaly was the uncompromising way in which the set presented his music: in session order and with alternate takes. That would be a familiar format to jazz devotees of artists like Charlie Parker, but was not typical of `folk blues’ releases. Columbia’s 1961 and 1970 Johnson Lps, King of the Delta Blues Singers, Vol. I & II, had been compiled for pacing and variety. (Interestingly, Vol. II started with Johnson’s first four recorded songs in order, but then strayed from that arrangement.) The strict session presentation of the Complete Recordings said: `This music is historically important. To understand it, you need to hear it in the order in which it was recorded.’

With the 80th anniversary of Johnson’s recording debut in mind, I decided to listen again to the sixteen songs he recorded in San Antonio in 1936. I wanted to pay attention to what he chose to record and in what order. Perhaps, as the Complete Recordings suggested, I would learn something from that.

Robert Johnson was 25 years old when he made his first recordings. He grew up hearing the first generation of recorded Delta blues singer-guitarists and was directly influenced by Son House, who also inspired Muddy Waters. He heard popular blues acts on record, too, and would prove adept at reworking their songs. Johnson, more than many of his contemporaries, appears to have been conscious of the recording process as something distinct from public performance. Particularly on his first day in San Antonio (Nov. 23, 1936), his songs sound like they were carefully crafted and polished for a special occasion.

“I’m going to Texas to make records,” Johnson reportedly announced to a sister on the eve of his San Antonio trip. He had auditioned for Jackson, MS talent scout H.C. Speir, who had been instrumental in steering Delta blues artists toward record companies since the late 1920s. Speir recommended Johnson to an American Record Corporation salesman-talent scout, Ernie Oertle, who drove Johnson to San Antonio, where ARC was doing location recordings.

San Antonio may seem an unlikely recording center today, but in the mid-1930s it was not. Western Swing bands were on the rise across Texas, as was the Norteño music of its Hispanic population. Black blues pianist-singers were also prevalent and popular in the Lone Star State, and, relative to the era’s big bands, none of these acts required dedicated recording studios. Two adjacent rooms in a hotel—one for the artist and the other for the engineer, producer and recording equipment—were sufficient.

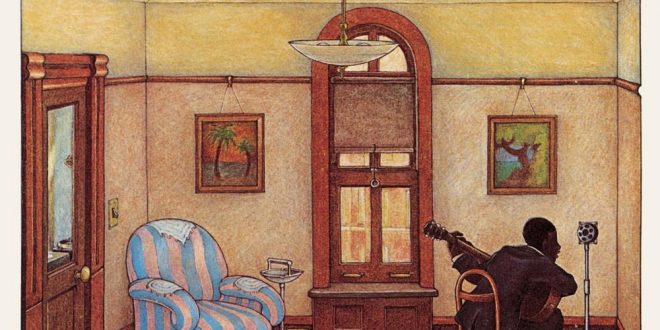

Overseeing the session was Don Law, who Lawrence Cohn describes as “a hired hand, a staff producer for the company whose area pretty much was the Southwest.” (Cohn produced the Johnson Complete Recordings box.) Law was the only one left to remember Johnson’s 1936 session when interest in him grew a quarter century later. He recalled Johnson as uncommonly shy, offering an anecdote in which he responded to a request to play for some Hispanic musicians by turning away from them as he played. Artist Tom Wilson was inspired by Law’s tale to depict Johnson recording while facing the wall on the cover of Columbia’s second Johnson LP.

If some of Law’s recollections have been deemed dismissive, it’s noteworthy that someone at ARC was impressed enough by Johnson to bring him hundreds of miles cross country to record sixteen songs, no small vote of confidence in a new and unproven artist. Johnson was reportedly the only artist recorded on the day of his debut, Nov. 23, 1936. He recorded eight songs, five of which he recorded twice, so there were thirteen performances that day. “I’ve often wondered what it would’ve been like to be standing next to Don Law and watching the process,” says Lawrence Cohn, who brought Johnson’s music to CD. “Did he actually say anything? Did he actually try to move Johnson in a certain direction?” The alternate takes suggest he did. Most are delivered at a brisker pace and with more bravado than the initial take, as if Johnson had been told, “Pep it up a little, Robert!” The one exception is the first song Johnson recorded and likely the one he deemed his most polished jewel, “Kind Hearted Woman Blues.” Rather than rush it, on the second take he drops his guitar solo, the only one he ever recorded.

“Kind Hearted Woman Blues” is carefully crafted, measured except when he sang falsetto for impact, blues chamber music of a sort. It’s tempting to imagine Law not knowing what to make of this and thus asking for that second take. By contrast Johnson’s next two songs were one-take wonders and future blues standards, “I Believe I’ll Dust My Broom” and “Sweet Home Chicago.” Both were Delta dance music, driven by Johnson’s steady right thumb and a boogie-inspired bass line, destined to become cliché but still novel on guitar in 1936. “Broom” is so identified with Elmore James that it’s surprising to hear the original and realize that Johnson didn’t play slide guitar on it. His mastery of slide first became evident on his next song, “Ramblin’ on My Mind,” one where the alternate take offers an interesting lyrical revision: “I’ve got mean things on my mind” became “she got devilment on her mind.”

“When You Got a Good Friend” delivered another walking bass groove and found Johnson uncharacteristically offering advice and asking forgiveness. “Come On in My Kitchen” was both seductive and profound: “So dramatic that it borders on being cinematic,” says Cohn. “The pauses and the drama and the way he approaches silence where the guitar is concerned, it’s just extraordinary.” Its `extraordinariness’ may have simply puzzled Law, who asked for a second take. The two takes have enough different verses between them that one imagines Johnson playing “Kitchen” in other settings for a very long time, drawing on a deep reservoir of interchangeable verses.

Johnson had two more songs to record on Nov. 23rd, and the first would be the closest he came to a hit record during his lifetime. “Terraplane Blues” is believed to have sold around 5,000 copies, enough to warrant calling Johnson back to Texas to record again in 1937. It’s tempting to peg “Terraplane” an early entry in the genre of R&B car songs, one that culminated in the inventive and influential work of Chuck Berry. But while Berry was constrained by what could be played on radio, Johnson was recording for jukeboxes and was free to indulge in salacious automotive double entendres (“I’m gon’ heist your hood, Mama, I’m bound to check your oil…”). “Terraplane” is the first of Johnson’s recordings to really reflect his deep Delta roots, both in its musical form and through his emotional delivery. You sense that, seven songs into his first day of recording, he finally loosened up.

“Phonograph Blues,” another mechanical double entendre lyric (“I want to wind your little phonograph just to hear your little motor moan”), closed Johnson’s first day of recordings. If `the medium is the message,’ per Marshall McLuhan, Johnson seemed acutely aware of the medium on which his music would be heard. It was the same means by which he’d learned many songs he reworked; soon, others would learn from his records. His second take of “Phonograph” is remarkable for tossing the guitar accompaniment heard on the first and subbing instead the accompaniment to “Dust My Broom”! That may have been his all-purpose dance accompaniment, easily framing many songs.

Johnson would record eight more songs in San Antonio, but not before taking a couple of days off. Odds are he wasn’t sightseeing: Don Law recalled bailing him out of jail, where Johnson was reportedly beaten and his guitar smashed. He returned to the Gunter Hotel Nov. 26, Thanksgiving Day, and recorded a single song, “32-20 Blues.” If Law’s jail saga is true, Johnson’s vengeful lyric of gun violence aimed at an `unruly’ woman sounds like a payback fantasy for what he’d just endured.

Friday Nov. 27 was Johnson’s last day recording in San Antonio, and offered a couple of surprises: “Last Fair Deal Gone Down” was a brilliant arrangement of a work song, unique in Johnson’s recorded repertoire, as was “They’re Red Hot,” which offered jazzy diminished chords and a sound akin to that of the Mills Brothers and other popular black vocal groups of the day. But the dominant sound that Friday was that of Johnson’s Delta mentors, Son House especially, casting a long shadow over the proceedings. “Cross Road Blues” offered the `straining preacher’ urgency that was a House hallmark with lyrics suggesting dread of being caught after sundown on `whites only’ turf during the era of routine lynching. “Preaching Blues” (with the curious subtitle, “Up Jumped the Devil”), is a House theme which threatened to run away from Johnson, whose version was near manic, while “Walkin’ Blues,” also drawn from House, is absolutely all you’d want of Johnson, his guitar and voice balancing passion and control, the performance overall a bold signpost towards the music’s move to Chicago with Muddy Waters. The day’s one forgettable song, “Dead Shrimp Blues,” demonstrated Johnson’s attraction to oddball double entendres, while his final San Antonio recording, “If I Had Possession Over Judgment Day,” was a striking performance (“Rollin’ and Tumblin’” by another name) not issued on 78. “Why would a tour de force like `If I Had Possession Over Judgment Day’ not be released till Frank Driggs did the `60s Lp is unfathomable to me,” says Lawrence Cohn. “It was such an extraordinary outing, I thought.”

Johnson’s San Antonio sessions were, for the most part, extraordinary outings. Had he never recorded again he would still be remembered for the songs he brought to the Gunter Hotel, though his later Dallas recordings (“Me and the Devil Blues,” “Hellhound on My Trail”) did more to bolster the Faustian myth. It has been suggested that Johnson boasted of selling his soul to the Devil as a marketing ploy. But, Satan aside, his reputation as womanizer was his undoing: it’s believed he was poisoned at age 27 by a jealous husband. Months later producer John Hammond put out the word that he wanted Johnson to perform in the now-legendary Spirituals to Swing concert at Carnegie Hall.

Johnson’s early death proved a bad career move in the short term, though it became an important element in the romantic mythology that framed his music. Critics of that mythology dismiss it as a white fantasy of black exoticism, Johnson tricked out as a kind of Rimbaud of the Delta. The fact that Johnson may be the only blues artist pre-B.B. King many Americans have even heard of rankles those who point to the artists who influenced him and regard the King of the Delta Blues Singers crown as better deserved by Johnson’s antecedents (Son House, Charlie Patton, etc.). Johnson’s iconic status can also be questioned in terms of how few records he sold to black 78 buyers in his day and the limited number of artists he influenced (though one Muddy Waters may count for a dozen lesser lights). It can be argued that, though he was first to record some later standards, the songs only became known thanks to later, `hotter’ recordings. And there’s no denying that Johnson’s popularity during his day was overshadowed by several great and influential blues singer-guitarists, among them Lonnie Johnson, Tampa Red, and Big Bill Broonzy. But who among them have had a hotel bar named after a room where they recorded? 80 years on, that surely counts for something…

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California