The guitar hit its zenith of power and popularity in the 1960s. In the decade’s shiny early years the spare twang of Duane Eddy and the propulsive throb of surf guitars were recurring motifs in America’s soundtrack. By the decade’s turbulent climax, the swirl of psychedelia was driven by guitarists elevated, much to their peril, to pop culture deities.

The foundation for the guitar’s grand decade had been laid in the late 1940s by T-Bone Walker, Les Paul and Chet Atkins: they developed guitar languages eagerly emulated by the first generation of rock guitarists. Pianos were vehicles for several rock pioneers, but you couldn’t duck walk with a baby grand. Chuck Berry, along with Elvis’s right hand man Scotty Moore and many others, made the guitar the insistent instrumental voice of rock `n roll. By the end of the Fifties rock instrumentals had gained popularity, and while some featured saxes and organs, nearly all starred guitars. The stage was set for the guitar’s absolute ascendancy in the Sixties.

All this mainstream noise was delivered via electric guitars. Had the acoustic guitar completely withered and died? No, it too was wildly popular, for good reason. Every kid who aspired to be the next Elvis could wiggle and bang on a cheap acoustic, more easily purchased with paper route money than an electric and amp. Then there was the increasing popularity of an alternative to rock: in 1958 the Kingston Trio scored a pop hit with “Tom Dooley.” They backed their pseudo-Calypso rendition of a murder ballad with banjo and guitar, unplugged. The urban folk music movement, squelched in the early Fifties for its Left leanings, was robustly reborn. Acoustic guitar sales skyrocketed.

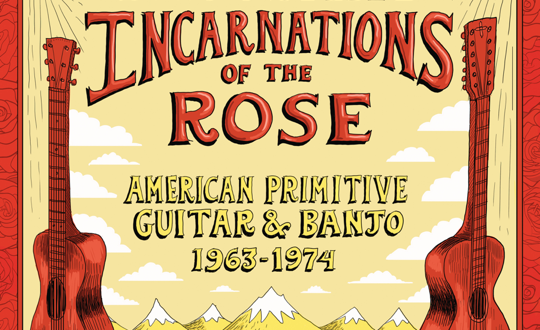

Fortunately, what was played on them was not limited to Kingston Trio covers. We’re reminded of that in two outstanding new releases of `60s vintage performances, The Thousand Incarnations of the Rose: American Primitive Guitar & Banjo, 1963-1974 (Craft Recordings) and Doc Watson Live at Club 47 (Yep Roc Records). The first is an ambitious compilation of recordings of what may loosely be called a `school’ of music, while the second is a previously-unissued `live’ performance by one of America’s greatest folk musicians.

Fortunately, what was played on them was not limited to Kingston Trio covers. We’re reminded of that in two outstanding new releases of `60s vintage performances, The Thousand Incarnations of the Rose: American Primitive Guitar & Banjo, 1963-1974 (Craft Recordings) and Doc Watson Live at Club 47 (Yep Roc Records). The first is an ambitious compilation of recordings of what may loosely be called a `school’ of music, while the second is a previously-unissued `live’ performance by one of America’s greatest folk musicians.

The Thousand Incarnations…brings together seventeen performances by eleven different artists deemed by compiler and annotator Glenn Jones to be standouts of the American Primitive genre. And what might that be? John Fahey (1939-2001) may not have coined that term to describe his guitar style, but he bore the brunt of explaining it: it became what now would be called his `brand.’ When I interviewed Fahey in 1980, he told me: “I stopped using that term because it was so badly misinterpreted. I didn’t mean primitive in the sense of raunchy. There are schools of primitive painters, like Grandma Moses, which just means untutored, and that’s how I meant it.” Fahey may have been untutored, but that in no way limited his aspirations. “My overall approach is that I’m playing a concert of suites or symphonies,” he said, chafing at being lumped with folkies: “I don’t think of myself as in that bag,” he said, “because what folk musician ever got up and played 20-minute suites or symphonies?”

Mercifully, Jones spares listeners those long form works. Instead, he opens his collection with Fahey’s lean “Night Train to Valhalla,” a stunner encapsulating the American Primitive guitar ethos is just over two minutes. It opens with a spare and angular statement that evinces an awareness of such astringent 20th century composers as Alban Berg. Then Fahey rips into a reimagining of one of the train tunes of pioneering country fingerstyle guitarist Sam McGee (“He was the guy I tried to copy the most…He was so clean and fast, so good all around”). This rollicking section has plenty of what Leo Kottke calls `torque.’ Then, with classical `theme and variation’ in mind, Fahey returns to close with his icy opening statement, a succinct glimpse into what he called the Void: “It’s how you feel when the bottom drops out,” he said. “It’s worse than the blues. Some of the music I’ve written is a description of that state.”

“Night Train…” is immensely appealing for its brisk brevity and overall simplicity, but it’s also illustrative of the radical reach of the founding American Primitive guitarist. It’s been so long since this was new that we have to remind ourselves that steel string guitarists who didn’t sing were once anomalous. When Fahey grew up, steel-strung guitars were associated with Hollywood’s singing cowboys strumming by celluloid campfires. The guitar was a folksy prop, not the center of attention. Fahey aspired to elevate the steel string guitar to the level of art instrument, utilizing his knowledge of folk-and-blues-based fingerstyle guitar techniques and varied tunings in tandem with his informal grasp of classical music. He may have been untutored, but he was surely not unambitious.

We may never know if there were also John Faheys of the tuba or accordion whose misfortune was aiming to expand the horizons of instruments not `hot’ in the Sixties. But Fahey had the Right Stuff at the right time, and his obsessive pursuit of his quirky vision led him to found the Takoma label, which became a magnet for like-minded artists. “This cheap cassette with a lot of distortion came in to us,” he told me. “I listened to it and said, `Wow, that’s beautiful music, and I bet it would sell.’” That cheap cassette morphed into Leo Kottke’s 6 & 12-String Guitar, Takoma’s biggest hit. Two 1968 outtakes from it appear on The Thousand Incarnations… “The Ice Miner” is in 3s and has an agreeable lilt. “Anyway” is a lyrical 12-string slide guitar piece played with plenty of what Kottke called `vertigo’ and `swoop.’ Perhaps unconsciously, it echoes the Sleepy Lagoon feel of some 1920s-vintage Hawaiian guitar music. Look elsewhere to hear Leo’s trademark `torque.’

If Fahey and Kottke were Father and Son of the Takoma Trinity, then surely Robbie Basho (1940-1986) was its Holy Ghost, in the sense of a being beyond ready comprehension. Fahey delighted in telling a tale of Basho refusing on one occasion to set foot in Takoma’s studio before the `bad vibes’ that had settled into the carpet had been thoroughly vacuumed up. Kottke remembered him fondly: “He had a big effect on me,” he said. “He had an old 12-string guitar and used to wear cowboy outfits and carry around Japanese movie review books. One night at a place called the Unicorn I was following him and I said, `Gee, I’m really kind of nervous, because I’ve been listening to you so much, I’m afraid I’m going to sound a lot like you.’ And he said, `Aw, that’s alright, we all go through somebody sooner or later.’”

Basho may have had synesthesia, `hearing’ colors. Inspired by the Indian raga system, with its associations of intervallic relationships with specific emotions, times of day, and deities, Basho developed charts describing relationships he divined in chords and guitar tunings. Here’s an example from his Modal Tunings Chart:

– Chord: Am

– Color: red rose to scarlet

– Mood: Deep passion

– Concomitant Properties: dark rose Madonna of the Gypsy caves

Basho told me, “I took lessons from a Gypsy, a real Gitano.” Flamenco technique informs the opening of Basho’s meandering “The Thousand Incarnations of the Rose,” arguably a better title than performance. Compiler Jones calls it Basho’s “attempt to express something not yet quite within his grasp.” Along with flamenco it also references Japanese Koto music and much else in a not-quite-cooked way. It’s tempting to dismiss the nearly 14-minute long “Incarnations…” as unfocused noodling masquerading as afflatus, but Jones calls it “a gripping and suspenseful performance,” so it’s all in the ear of the beholder. Certainly Basho knew what he was aiming at: “My gift is texture,” he told me. “Go to a part of the country, feel the texture in the air, and put it down in tone on the guitar. It’s striving for a new form, for an extraordinary feeling. I’m trying to paint pictures of America…”

These Knights Errant of American Primitive guitar roamed an America more akin to Kerouac’s than our own. In the Sixties there were still cross-country coffee houses in which they could find small but appreciative audiences for their unlikely blend of folk techniques and eclectic musical influences. It was a congenial environment in which to develop what was essentially an `underground’ art form. The intimate `live’ venue was the crucible in which they evolved, but Fahey foremost among them understood the heady `secret sauce’ to be served in the recording studio. “I think of the guitar as a whole orchestra,” he told me. “It sounds like an orchestra, especially with a good PA system.” Or with a good recording engineer. Fahey had heard the recordings Andrés Segovia made in the 1950s for Decca, recordings which added a lot of `room’ to the nylon-strung classical guitar, its notes notoriously prone to rapid decay when recorded `dry.’ Fahey took Segovia’s enhancement and ran with it, as witnessed by the closing tune on Incarnations…, “The Portland Cement Factory at Monolith, California.” Engineered with reverb that rings without overpowering the music, Fahey got his guitar recorded so that you feel as if you’re listening from inside the sound hole. For my money that’s his (and his engineers’) little-cited contribution to the acoustic steel string guitar—Fahey made it sound BIG.

There are also some noteworthy banjo performances here. The eclectic multi-instrumentalist Sandy Bull showcases a variety of ways of playing the instrument in his arrangement of “Little Maggie.” George Stavis was unknown to me before his inclusion on Incarnations…His 1969 recording “Winterland Doldrums” is a performance I keep returning to for an intriguing blend of tradition-based simplicity and improvisation amidst a wide dynamic range. “I tend to think of what I do as a kind of soundtrack,” Stavis says in the album liner notes, “where the music is almost visual.”

Comprised of vintage recordings from the Takoma and Vanguard labels, not all of the seventeen tracks here have aged well. This was the psychedelic era: some homages to Indian music, though sincere, reek of stale patchouli oil, potential soundtracks to a `Jack Webb busts the hippies’ episode of Dragnet. There’s a slide guitar piece in which the player’s sense of pitch might charitably be called fluid. There’s an out-of-tune 12-string. There are times when charming naiveté careens recklessly toward sloppy amateurism. But let’s not forget: these players went fearlessly where none had dared go before them. Their goal was less virtuosity than vision. All too soon the American Primitive movement got co-opted by New Age guitar, elevator music for the Quaalude and chardonnay set.

Craft Recordings has lavished a lot of love on its Thousand Incarnations…production. Drew Christie’s cover art sharply echoes the psych-Americana zeitgeist of the old Takoma Lp covers. The CD version of the album is a very agreeable car companion. The double Lp vinyl set is a thing of striking beauty, offering Christie’s eye-popping illustrations, cover shots of the original Lps, and six pages of liner notes by compiler Glenn Jones. These were analog recordings, so it’s great to hear them on a turntable. The sticker on the vinyl edition shrink-wrap proclaims: “180 gram vinyl…Deluxe old-school style tip-on gatefold jacket and tipped-in book.” It feels lush.

As if all that weren’t enough, this reissue has a festival coming up with the same name to spread the word. Guitarist Glenn Jones had an active hand in that. He’ll be performing alongside many of the artists on his Thousand Incarnations compilation: Max Ochs, George Stavis, Peter Walker, Harry Taussig, and Peter Lang, a Fahey disciple who recorded for Takoma in the early `70s. They are among 25 fingerstyle guitarists and banjoists descending on John Fahey’s birthplace, Takoma Park, Maryland, for a three-day celebration of American Primitivism April 13-15th. It’s being touted thus: “A Music Festival Unlike Any Other. Marking the 60th anniversary of John Fahey’s first recordings in his boyhood home of Takoma Park, Maryland.” Fahey spent most of his adult life in California, but his birthplace will honor him both with a festival celebrating his music and by naming the auditorium in a community center for him.

https://www.facebook.com/AmericanPrimitiveGuitarFestival/videos/178953742909729/

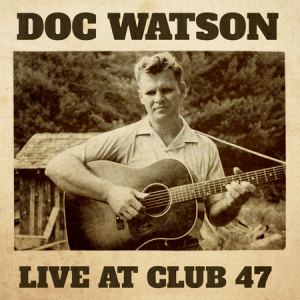

Fahey grew up in an affluent suburb of Washington, D.C. Arthel `Doc’ Watson (1923-2012) grew up in Deep Gap, North Carolina—the name says it all. Blind since infancy, Watson had taken up harmonica, guitar and banjo in childhood, and by 1953 was picking up change playing electric guitar in a country dance band and earning a little extra as piano tuner. His life might have continued like that had not folklorists Ralph Rinzler and Eugene Earle discovered Watson in 1960, playing in a group assembled by legendary singer-banjoist Clarence `Tom’ Ashley. Rinzler brought Watson to New York City for the first time in 1961, and the burgeoning folk scene welcomed Watson with open arms. Club 47 in Cambridge, Massachusetts was one of the era’s primary folk venues: Joan Baez got her start playing there in the late `50s. It proved to be an especially welcoming place for Watson. Rinzler recalled: “”When I was trying to get Doc started, it seemed right to go there as frequently as possible. People there really got into Doc as a person…It was like taking a bath in humanity when you came up to Cambridge. I really thought that our visits there were an extraordinary experience, and so did Doc.” Decades later, that experience still sounds extraordinary, proven by the first-ever release of 26 performances by Doc Watson Live at Club 47 (Yep Roc Records).

At the time of these February 1963 recordings, Watson was 39 and had yet to make his first studio album for Vanguard. He was still getting acquainted with the urban folk audience, but surely sounds like he’s enjoying himself. “That’s better than money for the pay,” he says after a round of applause. “I love to pick! I really love to pick.” That love was mutual: Watson continued wowing audiences for nearly five more decades, but there’s something especially appealing about the freshness of his early performances, when he and his audience were first getting to know each other. It’s just Watson, his voice, instruments, and folksy commentaries. “It’s a little trouble to change the wires on this thing for that song,” he says while re-tuning his guitar to fill a request, “but it’s worth it e’er you get `em there.” A downhome folklorist himself, Doc plays both the A and B sides of the first 78 released by `the pride of West Virginia,’ Frank Hutchison, in 1926 (“Train That Carried My Girl from Town”/“Worried Blues”). Watson understood that the folk audience looked to him as a paragon of authenticity, but he made it clear to listeners that he arranged the vintage material he performed his way: Introducing “Wabash Cannonball” as a Carter Family song, he then says: “I’m not gonna do it like the Carter Family, this won’t sound a bit like `em. This’ll be according to Doc.” Several times in the course of this `live’ performance he makes that point, pleasantly but firmly: `I may be performing what you consider a folk song, but this is not a generic rendition, it’s a specific arrangement by Doc Watson.’

Some of the pieces most associated with Watson’s stamp—his fleet flatpicking of the fiddle tune “Black Mountain Rag,” his Travis-picked version of “Deep River Blues”—are here, but so are songs he never recorded in the studio or performed in later years. These range from the rollicking “Old Dan Tucker” to the English ballad “Little Margaret,” accompanied by banjo. There’s even one instrument he never took into a recording studio, the autoharp, played on “Little Darling Pal of Mine.” We’re reminded of how effective Watson’s harmonica-guitar interplay could be on the powerhouse performance of “Sweet Heaven When I Die,” as well as others heard here. And there’s “Days of My Childhood Plays,” where Watson’s voice uncannily echoes that of Alfred Karnes, who recorded the original in 1928 and who, like Watson, was blind.

Ralph Rinzler’s mandolin accompanies Watson on three tracks here, and John Herald plays second guitar on five. But the spotlight is clearly Watson’s. He was at the peak of his powers, and filled a unique niche in the `60s folk revival: he wasn’t a rediscovery, an old man recorded commercially decades ago, honored for his place in history but clearly past his prime. Watson was a professional musician who could have held his own with the era’s Nashville session players but who found himself thrust into the urban folk music milieu, which suited him just fine. There was no one else on the scene delivering old-time country (and folk and blues) with his blend of originality, flair, and deeply-rooted authenticity. And the fact that he was still proving himself in 1963, casting a wide net, means Live at Club 47 offers a range of material and instrumentation not heard in his later studio recordings. Watson’s deepest influence would be on generations of flatpickers who followed his lead in adapting fiddle tunes to acoustic guitar (he had a knack for playing fast without feeling rushed), but this reminds us there was far more to him than that. The 28-page booklet accompanying Live at Club 47 offers half a dozen wonderful photos of Watson, who had a craggy Rushmore-worthy face, and thorough liner notes by Mary Katherine Aldin. She expertly frames Watson in relation to the era’s folk scene and traces the background of each of the songs. Doc Watson Live at Club 47 is an exemplary work all around: it’s tempting to label it an `historic reissue,’ but it’s not, since few have heard these previously-unissued recordings since they were made 55 years ago, which makes them all the more exciting.

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California