For sky watchers anyway, it was big news: On Oct. 18 the moon passed over Aldebaran, a giant star (“the bull’s fiery eye in the Taurus constellation” is one description) in an event visible across much of America, one called an `occultation.’ A site called Space.com anticipated it with dramatic flair: “As the moon, three days past full, ascends the eastern sky, Aldebaran will appear to creep up to the moon’s bright limb for many minutes, then hang on the sunlit edge for a few seconds — an eerie orange fire among the lunar hills… Then, in an instant, it will snap out of view. Aldebaran will reappear from behind the moon’s dark portion (depending on your location) up to 75 minutes later.”

I missed that celestial show, but caught an even rarer one two months prior at the Grammy Museum: an appearance by Judy Henske and Jerry Yester to promote the Omnivore Recordings reissue of their 1969 album Farewell Aldebaran. “It was like a fist of an idea,” Henske said of her discovery of Aldebaran in an encyclopedia. “Aldebaran’s a star that’s a red giant,” she continued. The EarthSky site dares you to wrap your head around this: if Aldebaran were “placed where the sun is now, its surface would extend almost to the orbit of Mercury.” And it’s 153 times brighter than the sun! Admittedly not typical song lyric fodder, Farewell Aldebaran was no ordinary album.

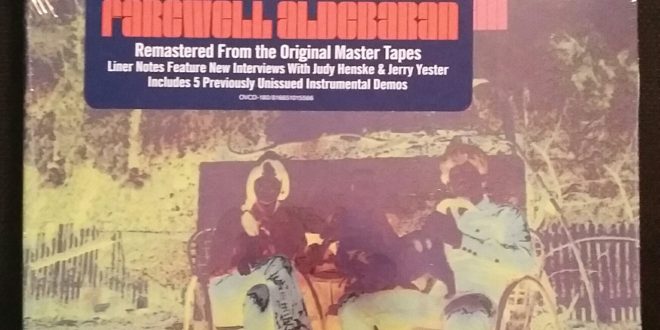

It debuted two years after the Summer of Love in the over-amped summer of Woodstock and the Manson murders. Unlike those cataclysms Farewell Aldebaran caused no stir at that heady time: unlike its giant star namesake it sank swiftly without trace. But just as an earlier generation of record collectors had championed obscure blues artists, known only by scant and scarce 78s, collectors of `60s psychedelia have discovered and championed Farewell Aldebaran. And these current collectors share their passions via the internet. “My obsession with the album was immediate and very potent,” enthuses one René Kladzyk, “and has only grown with repeat listens.” Jon Dale, who likens the album’s solarized cover photo to “a carapace of psychedelia,” neatly summarizes the album’s effect: “The whole thing is faintly alien in tone and psychedelic in the truest sense—opulent and temporarily dislocating.” There are hosts of online testimonials to (and dissertations on) an album dubbed “one of those legendary lost records that everyone talks about.” An unwanted orphan when released, the original LP became a sought-after collectible. Unsurprisingly bootleggers in Europe brought it to CD.

47 years after it first flopped, Omnivore Recordings resurrected and released a remastered Farewell Aldebaran in August on both CD and vinyl. It was deemed sufficiently noteworthy that the Grammy Museum in downtown Los Angeles hosted an evening with Henske and Yester. Music journalist Steve Hochman interviewed them prior to their performance.

That was the first time Henske and Yester had performed many of the songs since recording them: there was no tour in 1969 to support an album that vanished on release, so this was an album launch nearly a half century after the recordings! Married when they recorded Farewell Aldebaran, Henske and Yester are decades divorced. Someone in the audience asked: “What has it been like to reconnect?”

Yester: “Terrifying.”

Henske: “Ugly.”

Only their family and friends knew if they were kidding or not.

The two met in 1962 when the `60s folk boom was in full flower. Henske was making a name for herself as a brassy folk-blues diva, influencing every white female blues singer who followed (it’s hard to imagine Janis Joplin without Henske). Yester had been in the New Christy Minstrels and would work in the Modern Folk Quartet, named for the Modern Jazz Quartet, noted for its `chamber jazz.’ The MFQ aimed for a similar eclecticism. By 1969 the folk boom was a mere memory. Henske had tried unsuccessfully to transition to pop in some stunning (but unsuccessful) recordings with legendary L.A. producer Jack Nitzsche. Yester was arranging and producing for the likes of the Association and Tim Buckley and performing with the Lovin’ Spoonful. The two were new parents to daughter Kate, and the project that became Farewell Aldebaran was perfect for two essentially stay-at-home parents. Henske, a lifelong poetry lover, would write the lyrics and sing most of the songs. Yester crafted the music and coproduced the recordings with ex-Lovin’ Spoonful member Zal Yanovsky.

“We expected to get rich from this,” Yester said in answer to a question about their hopes for the record. “I had already picked out a new bicycle.” OK, maybe he was kidding. But they did at least hope to be noticed, and pulled out all their creative stops. “It was vaguely terrifying,” Yester recalled. “The more varied it was, the better.”

Some of the album’s online admirers have commented that its ten tracks sound like the work of ten different bands. “It was like a variety show of an album,” Yester said. “We both came out of folk music [where] no two songs are alike.” Asked by interviewer Hochman if the album had an overarching theme, Henske replied: “You don’t need a theme on a record. You have different moods.”

Those differences are stark in the songs, and the Henske-Yester discussion revealed just how dissimilar recording them could be. The album’s rocking opener, “Snowblind,” “kind of happened in fifteen minutes,” said Yester. “It took very little time to come together.” By contrast the album’s title song, which Yester sang, was one of those recording studio art projects that threatened to never congeal: “We mixed the song `Farewell Aldebaran’ 13 times,” he said, until they felt they finally had it right.

Henske has a special fondness for her Gothic lyrics to “Lullaby,” and applied her dark wit to introducing it: “`Lullaby’ is to put a baby to sleep—permanently,” she said. “It’s got this creepy witchiness. If your baby’s not crying at the end, we didn’t do our job.”

The job of bringing the songs of Farewell Aldebaran to performance was daunting. For one thing, said Yester, “Living 1800 miles apart makes rehearsal a bitch.” For another it was very much a multi-layered studio album, not the sort of thing easily recreated on a reissue label’s budget. At the Grammy Museum Henske sang and Yester played banjo or guitar to instrumental tracks from the album. Henske’s husband of 44 years Craig Doerge played keyboards on some songs, and a host of family members sang along on their closing song, “Raider.”

It was the culmination of a lot of work: Yester reckoned it had been ten years since the first glimmer of interest to the night of the Grammy Museum performance on the day on the Omnivore label reissue (Aug. 11).

“They said, `Do anything you want,’ and it sank like a stone,” Henske said of the Straight label, a venture between her manager, Herb Cohen, and Frank Zappa. “We put everything we had into this album. It came out, and…nothing!” If Straight had a promotion budget, it wasted none of it on Farewell Aldebaran. “I thought it was so worthwhile,” Henske mused, “and it just disappeared.” She may now walk with a cane and be largely blind, but Henske’s stage timing and humor are undiminished. At the Grammy Museum she asked and then answered a rhetorical question of her audience: “Do you know who we were sacrificed on the altar of? You know who came out on Straight at the same time? We were sacrificed on the altar of Alice Cooper. [Pause] Who is a pretty good golfer.”

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California

Baja Review A community newspaper serving Ensenada, Valle de Guadalupe, and Rosarito in Northern Baja California