Ever buy a calendar for how it sounds? For fourteen years now, some blues fans have been doing just that. Blues Images delivers a calendar adorned with vintage advertisements for `new’ blues releases accompanied by a CD of the music being advertised, plus several extra tracks. The calendar’s producer is John Tefteller, a blues collector whose fanatic devotion to the hunt for lost 78s is the stuff of legend, celebrated at length in Amanda Petrusich’s book, “Do Not Sell At Any Price: The Wild, Obsessive Hunt for the World’s Rarest 78rpm Records” (Scribner; 2014).

In 2002 Tefteller struck a visual motherlode in Port Washington, Wisconsin: over 4000 vintage advertisements for blues and jazz recordings, many not seen since the 1920s. That was the catalyst for his annual Blues Images calendar, augmented by recordings from his massive record collection. Each year, Tefteller offers something fresh on both the visual and musical fronts to encourage return business. It may not have made headlines, but the appearance on the cover of the 2004 Blues Images calendar of a studio portrait of Charley Patton was Big News among Delta blues fans: except for the head and shoulders part of the photo, it was previously unseen. The 2015 calendar’s CD offered both sides of a Tommy Johnson 78 for which Tefteller paid a whopping $37,100. The calendar’s first pages reproduced its labels and offered Tefteller’s breathless account of the eBay bidding which led him to shell out “the highest price ever paid for a 78 rpm record!” At times the emphasis on rare, `only known copy’ recordings borders on the absurd: the 2014 calendar CD offered both sides of a battered, barely listenable Blind Blake 78, but the advert for one of those songs, “Miss Emma Liza,” was the year’s featured image.

This year it’s one selling a Memphis Minnie song, “I’m Talkin’ About You,” one of several from a 2015 Tefteller purchase of more long-unseen blues record adverts, this lot from a Boston rare book dealer. Some of these new images aren’t as detailed as many he’s used in the past, though his apology for one (“crudely drawn”) really only applies to a poor pen-and-ink likeness of Patton’s studio portrait aimed at selling one of his sacred songs, “Lord I’m Discouraged.” The artist should have been.

The 23-track CD of Blues Images Vol. 14 offers fresh `recently discovered’ tracks and rarities, but it also offers songs familiar to vintage blues fans in markedly improved sound quality. 2017’s calendar is Tefteller’s second to hype a restorative `secret sauce’ which brings out as much music as possible in these recordings’ battered grooves while minimizing the surface noise typical of old 78s. Having first heard Skip James’ “Illinois Blues”/”Yola My Blues Away” on a straight 78-to-Lp transfer with surface noise akin to a hail storm and the music an auditory equivalent to a blurry photo, I have to admit that his `secret sauce’ is potent stuff indeed.

Of course the improved sound only matters if you care about this music, and it’s certainly not for everyone. Tefteller’s real passion is for the `hard stuff,’ signaled by opening his 2017 compilation with Garfield Akers’ “Cotton Field Blues, Parts I & II,” an extraordinary performance which exists in some uncharted netherworld and which likely sounded archaic even when it was cut in 1929, hence the title (there’s no `cotton field’ in the lyrics, so the title may imply `old-timey’). Akers’ straining vocals and hypnotic guitar aren’t typical blues, and Tefteller’s selections demonstrate the way in which anomalous performers like Akers had their brief moment in the late 1920s-early 1930s even as more `standard’ blues was evolving. Memphis Minnie’s “I’m Talkin’ About You” suggests the broad outlines of what would become first-generation rhythm & blues, underscored by the way Chuck Berry reinvented her song in 1961 (rest assured the Minnie song is far louder and clearer on Blues Images Vol. 14 than on YouTube).

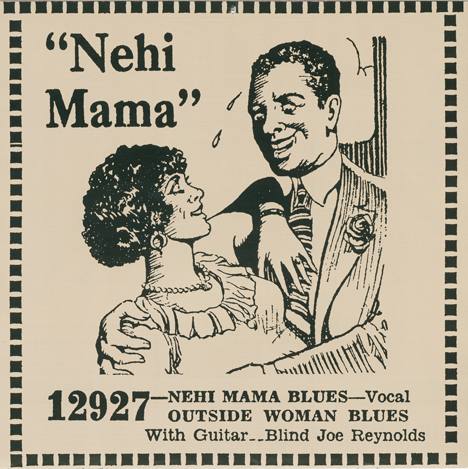

Singer-guitarists, from the influential Big Bill Broonzy to the quirky Blind Joe Reynolds, are foremost on the Blues Images collection, but there are a couple of stellar harmonica and piano performances and even a black string band, the Mobile Strugglers. Aficionados who have been listening to some of these tracks for years will be amazed by the fresh clarity of sound, and newcomers to the music will be able to like it or not on the merits of the music without undue distraction by surface noise.

As for the calendars’ 1920s ad imagery, Tefteller has in effect apologized for it: “We understand that African Americans in today’s society may be offended by some of the images here,” he wrote in a preface to his 2005 calendar. Obviously racial sensibilities in the 1920s were radically different, and much of the imagery smacks of racist stereotypes. Tefteller’s defense is that, by pairing the ad images with the music the ads promoted, we gain a fuller sense of the world this music inhabited. Nearly ninety years since some of this music was recorded, it seems less amazing that some of the ads appear dated or perhaps benignly racist (they were aimed at black buyers) than that this music was once deemed commercial enough to rate advertising at all. But it was, which is why the annual Blues Images calendar is a valuable insight into a fascinating if at times mysterious chapter in American musical history.