“Death,” Rev. Gary Davis sang, “don’t have no mercy.” It may be a cold admission on my part, but the passing of the famous, even of those whose work I greatly admire, rarely moves me much. It may cause reflection on their legacy, but unless I felt some personal connection, I seldom grieve at news of a celebrity passing. So I was surprised at my reaction to word of the death of Scotty Moore on June 28th. There was no reason I should have felt shocked, even if I didn’t know he’d been in ill health for some years. I never met Moore, he was 84 years old, and his major contribution to music was 60 years in the past. He had his moment. Yet I felt an irrational sense of loss at the news that the man who wrote the book on rockabilly guitar, Elvis’ first guitarist, had Left the Building.

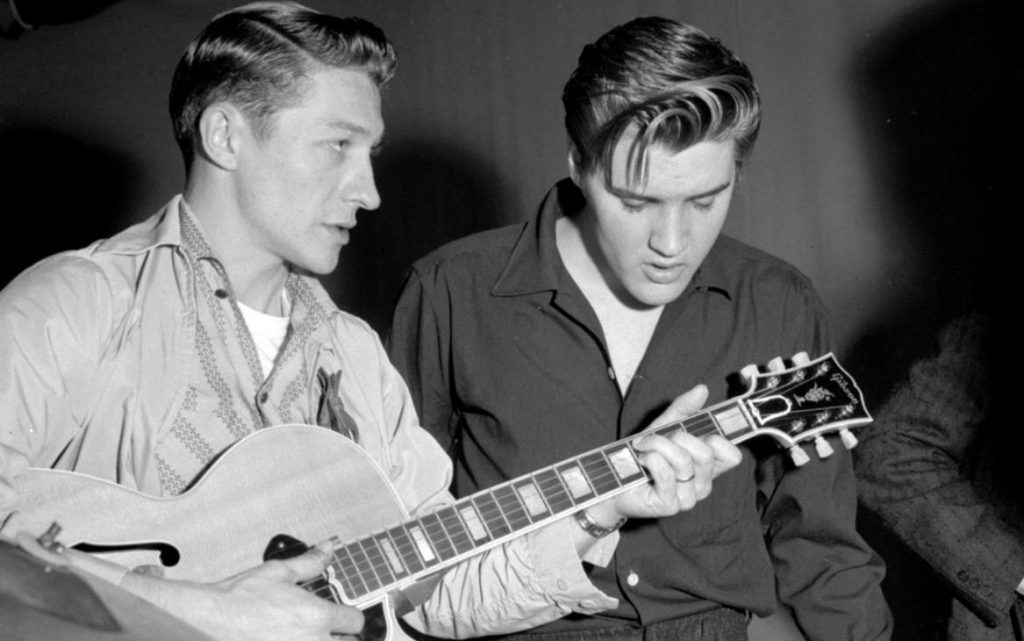

Maybe it’s because he was, as an atypically immodest album title put it, The Guitar That Changed the World. “Everyone else wanted to be Elvis,” Rolling Stone Keith Richards once remarked. “I wanted to be Scotty.” In reality there was no separating the two, not on the early Elvis records, anyway. Moore’s shimmering electric guitar, Bill Black’s standup bass, and Presley’s ragged-but-right rhythm guitar were the wings that gave Elvis flight. There’s no imagining the vital early Elvis, just 19 when he first recorded, without Scotty and Bill. Sonically, the three were one.

Scotty’s guitar solos especially were paragons of lean economy, always confident yet never flashy. The singer’s spotlight was never challenged. His playing was in the tradition of Southern fingerstylists Merle Travis and Chet Atkins, a lineage Scotty pushed to play a new blues-hillbilly hybrid. (Travis had been inspired by Piedmont bluesmen of the 1930s, of whom more later.)

That’s Alright, Elvis (Schirmer Books, 1997) is Scotty’s story as told to James Dickerson in the 1990s. To his credit Moore encouraged Dickerson to tell his tale as opposed to pretending it was a self-penned autobiography. Dickerson maintains Moore never censored any unflattering comments (often from ex-wives), so That’s Alright, Elvis is a warts-and-all portrait of a decent guy with terrific drive and talent, sadly little rewarded.

Since Scotty comes across as having had far less ego than he was entitled to, I tend to believe his account of Elvis’ discovery, which gives more credit to Sun Records secretary Marion Keisker and to Moore than to Sun founder/producer Sam Phillips. The standard version has the visionary Phillips searching for an Elvis type, thinking, “If I could just find a white kid who can sing with a black singer’s passion, I’d make a million bucks.” But Phillips’ genius was less about planning than letting things happen. Elvis’ discovery was a happy accident: no one was sure the kid had anything much to offer till they began fooling with a jumped up version of Arthur `Big Boy’ Crudup’s “That’s All Right, Mama.” Phillips quickly got the recording played on a popular Memphis radio show, Red, Hot and Blue, and thus began Something Big.

The trio started out with a fair split of their performance income: 50% for the star and 25% each for his sidemen. (Moore could reasonably have asked for a bigger slice, as he was both the musical leader and Elvis’ first manager.) But vultures quickly descended on Elvis, and soon Scotty and Bill were royally screwed. Scotty’s comments in That’s Alright, Elvis indicate he took his lumps in stoic stride, but Dickerson leaves readers no doubt that Elvis, his widely reviled manager Col. Tom Parker, and Sam Phillips were all to blame for shafting the men who gave Elvis’ music the drive it needed to succeed. Helping Dickerson’s case is Moore’s penchant for detailed record keeping. His total income from 14 years of working with Presley (including recording dates and movies) was a paltry $30,123.72. Little wonder Moore disappeared into audio engineering, or that he sought solace in the bottle and too many wives. An ex-Navy man, he was prone to settle disputes with his fists (Jerry Lee Lewis can vouch for that). At least he enjoyed a late life measure of what was due him when famous fans like Keith Richards, Ron Wood, and Jeff Beck sought him out to perform and/or record.

I first experienced Scotty’s magic more than a decade and a half later than the generation that caught his sound’s first wave. I have a brother, nearly a decade my senior, to thank for leaving behind a cache of 45s when he journeyed off to college. I started going through them in my late teens, discovering the wonders of `50s R&B and early rock. I was knocked out by the likes of Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, but I had little curiosity about Elvis. I grew up when Elvis was cranking out inane movies intended, I reckoned, for viewing by none-too-intellectual teen girls. I figured I was too smart for Elvis, but what, I wondered, was this 45, “Mystery Train”? The title was tantalizing. So with some trepidation and dread I put it on my portable stereo and twisted the `play’ switch. After the opening hiss (still a favorite feature of 45s), on came Scotty’s urgent, echo-laden guitar gallop, Bill’s loping bass, and, airborne atop their energy, Elvis:

“Train I ride….sixteen coaches long…

Train I ride….sixteen coaches long…

Well, that long black train…got my baby and gone…”

This was no Elvis I’d ever heard: he was singing a folk-blues, its lyrics old as alligators, yet this was a wholly other sort of folk-blues. It wasn’t `rock’ by any definition, nor was it country or any handy genre. It was in the tradition of songs and tunes imitating the drive and rattle of rails, yet it seemed somehow to float. As Scotty and Bill bop, the record fades with Elvis squealing, then chuckling, presumably from sheer joy at having just surfed such a perfect sonic Scotty-Bill-Elvis wave.

“Mystery Train” introduced me to the ebullient Elvis before the bad movies and schlocky songs and his eventual inevitable embarrassing demise. I experienced him on a 45 issued by RCA as it staked its claim to his earlier Sun recordings: this had been the B side of Elvis’ last Sun single. I would later learn that “Mystery Train” was a reworking of a Little Junior Parker song of the same title, recorded earlier for Sun. That’s a fine recording, one that bears a deep Delta blues grounding. The Elvis-Scotty-Bill train lit out instead for unknown territory.

Legend has it Bill Black kept a copy of the record on his wall and told visitors: “Ah, now there was a record!” Rock historian/essayist Greil Marcus named a book Mystery Train; director Jim Jarmusch borrowed the title for one of his films. The train pulls many coaches, and among its mysteries are the layers of music and culture that Elvis-Scotty-Bill magically encapsulated in their 1955 recording. One layer is the fingerstyle guitar approach Scotty took from the Merle Travis school. Travis generously acknowledged his own precursors, among them a North Carolina street musician, Fulton Allen, who recorded as Blind Boy Fuller in the 1930s. He was an associate of another blind street singer who would have a profound impact on the 1960s folk revival, Rev. Gary Davis.

Davis’ unlikely saga is told in a recent biography, Say No to the Devil: The Life and Musical Genius of Rev. Gary Davis (Ian Zack, University of Chicago Press, 2015). The South Carolina-born singer-guitarist migrated north to New York City, where he would become hero to a flock of adoring folkniks eager to touch base with authenticity. You can’t get much more authentic than a blind black gospel street singer. Author Ian Zack traces Davis’ life in minute chronological detail, and the insights and anecdotes of his one-time students are illuminating and often funny. The result is both a fascinating portrait of a remarkable contradiction-ridden character (the Rev. was as profane as sacred, famously feeling up women and toting a gun) and an account of a largely harmonious collision of cultures, those of Davis’ earnest educated white acolytes and his transplanted black Southern Baptist church milieu. Zack insists a mite too ardently that Davis was the folk-blues guitarist nonpareil, though there’s no denying that the Rev.’s playing, near baroque in its complexity, remains a thing of wonder. That, and his intensely sung songs, inspired everyone from Peter, Paul & Mary to the Grateful Dead, so the Rev. rates his own private coach on the Mystery Train.