Author John Wirt tells such a tale in Huey “Piano” Smith and the Rocking Pneumonia Blues (Louisiana State University Press). Wirt extensively interviewed Smith and the myriad musicians and malefactors who played roles in his star-crossed saga. He mainly lets their voices tell the tangled tale, even allowing the villains of the piece to defend their exploitation of Smithʼs work. Amidst flocks of vultures and losing legal battles that drove Smith to religious reclusion, the positive revelation here is Smithʼs central role in the vibrant New Orleans R&B scene of the 1950s and his musicʼs impact on R&Bʼs future. As Dr. John observes: “I credit Huey with opening the door for funk…”

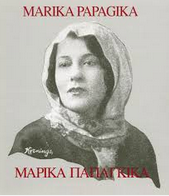

No such long-range influence can be credited to Greek-American singer Marika Papagika. Yet she made over 200 recordings, most for major labels, so her popularity likely transcended a narrow ethnic market. Itʼs easy to hear why: Papagikaʼs was one of the great voices of the 20th century. It balanced power and vulnerability, control and passion in amanner thoroughly disarming to this day. Few singers of any era pack an emotional wallop comparable to Papgikaʼs on “Galata Manes (smyrneiko),” one of eleven astonishments offered on the vinyl-only release Marika Papagika: The Further the Flame, The Worse It Burns Me: Greek Folk Music in New York City, 1919-1928 (Canary Records 003/Mississippi Records 051).

One of the extraordinary musicians who accompanied Papagika was violinist Alexis Zoumbas. He too had a knack for conveying a sense of passionate abandon with absolute control (and perfect intonation). Along with his accompaniments to Papagika and other New York-based Greek singers, Zoumbas `starredʼ on several instrumental recordings, a dozen of which appear on Alexis Zoumbas: A Lament for Epirus, 1926-1928 (Angry Mom Records AMA 04, available on vinyl and CD). The craggy northern Greek region Zoumbas hailed from is noted for “cultivating the most powerful music the world has scarcely heard,” Christopher King writes in his notes. Kingʼs obsession with Zoumbas is the focus of those notes: We follow King on a journey to Epirus, meet Zoumbas kin, even see a photo of `the foundation of Alexis Zoumbasʼ ancestral home.ʼ Itʼs a textbook example of how rediscoveries are primarily gifts to rediscoverers. But stunning performances like “Kleftes (Banditʼs Dance)” tell us why King was inspired to track this obscure sideman to his source. Zoumbas was the sort of master who balanced perfection on a pinhead. Hearing is believing.